I am not surprised that the idea of pegging the Ringgit has been raised again in the last few days. Refer to the latest article here, where the Finance Minister II was asked about the possibility of pegging the Ringgit.

As most analysts in town keep emphasizing, the depreciation of the Ringgit is not an isolated case. The chart below illustrates that most major and emerging market currencies are also experiencing the same trend as the Ringgit.

To peg or not to peg?

TL;DR: No. I am echoing what the Fin Min II answered:

“When we pegged the ringgit to the US dollar in 1998, we were reacting to a very different scenario and a very different financial capacity of the country. But today, when you look at the country’s reserves, the debt exposure and the financial liquidity in the market, Malaysia does not need to peg its currency.

Yes, it is a different situation indeed, but most people fail to see this.

Let's travel back to 1997: Two key reasons why it was necessary to peg.

Reason#1: Sharp deprecation and volatile movement of the currency

In response to the financial crisis initially triggered by the floating of the Thai Baht, the Ringgit depreciated sharply (refer to the table at the bottom of this post for the trend). Coincidentally, Bank Negara Malaysia did raise rates, but realized that this method was not effective enough to support the Ringgit due to external factors (Ariff & Yap, 2001). This might explain why BNM isn't responding to the depreciation of the Ringgit now by pushing up the OPR.

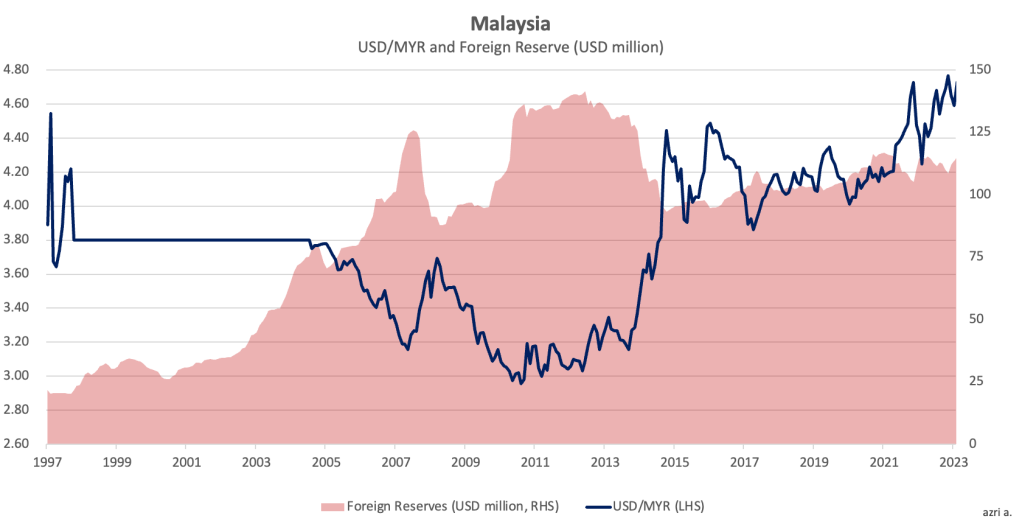

Then, from September 1998 until October 2005, the Malaysian Ringgit was pegged at 3.80. The figure below illustrates the trend of the Ringgit against the US Dollar over the years.

Furthermore, the total external debt was relatively high prior to the crisis, standing at around 58.5% of the GDP, as illustrated in the chart below. While it is noted that the latest numbers show that external debt stood at 68.2% of the GDP as of December 2023, bear in mind that if the currency depreciated in a matter of days, debt repayment, especially in foreign-denominated debt, would be much higher. In other words, a quick response was needed back then.

Reason#2: Import inflation

Due to the sharp depreciation of the currency, there was concern about imported inflation (Jomo Sundaram, 2006). At that time, it was a significant concern because Malaysia's economy was running a current account deficit prior to the financial crisis. As a result, inflation in June 1997 was around 2.4% and increased to around 5.7% in June 1998.

In comparison, we have been running a current account surplus for the past two decades.

To summarize, the table below illustrates the trends between two different periods: the Asian Financial Crisis from September 1996 to June 1998, compared to the recent trend of the last eight quarters. We can observe that the structure of the economy and the financial sector has evolved over time.

Sources:

Mohamed Ariff & Michael Meow-Chung Yap, 2001. "Malaysia – Financial Crisis In Malaysia," World Scientific Book Chapters, in: Tzong-Shian Yu & Dianqing Xu (ed.), From Crisis To Recovery East Asia Rising Again?, Chapter 9, pages 305-345, World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd..

Sundaram. (2006). Pathways Through Financial Crisis: Malaysia. Global Governance, 12(4), 489–505.

Great stuff! Keep writing please!